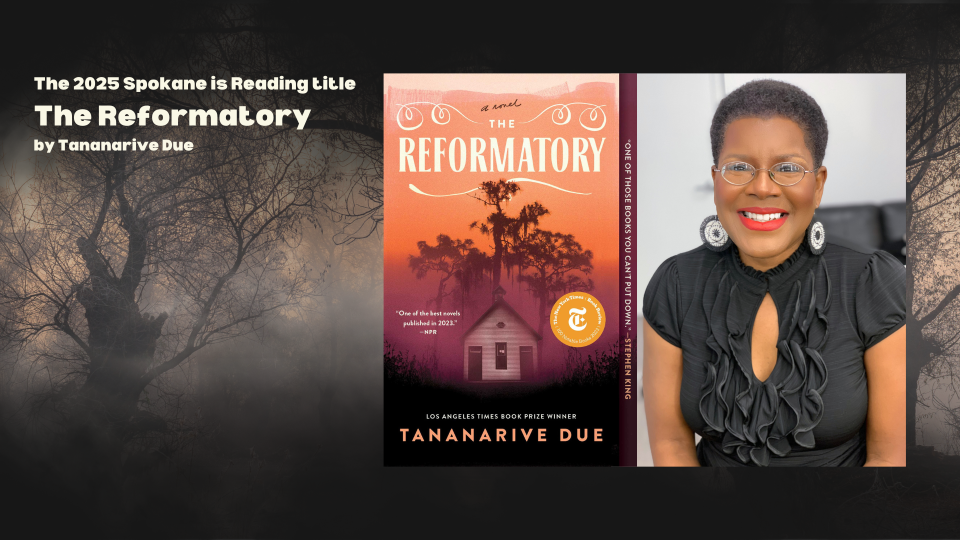

The Looking Glass: An Interview with Spokane Is Reading Author Tananarive Due

Posted on October 7, 2025 at 6:30 am

Guest post by Sharma Shields

Tananarive Due’s award-winning horror novel The Reformatory is this year’s selection for Spokane Is Reading.

You’re invited to a live watch party for a virtual talk with Tananarive Due about her book The Reformatory on Thursday, October 23, 1pm at Spokane Valley Library or 7pm at Central Library (get event details).

In great anticipation of these interactive, virtual author talks, I asked Tananarive Due a few questions over email, and the following are her wonderful responses.

Sharma Shields: The Reformatory exposes the crimes against children that happened at the Dozier School for Boys in the mid-1900s. Your great uncle Robert Stephens was one of the many victims at this school, and you honor him by name in this visionary and moving story. How did you first hear of your great uncle and how did you begin to transfer it with such imaginative power to the page?

Tananarive Due: In 2013, only months after we buried my late mother—and losing her remains the biggest personal horror of my life—I got a call from the Florida State Attorney’s office. For the first time, I learned that my mother had an uncle named Robert Stephens who died in 1937, at the age of 15, at the Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida. The true-life Robert Stephens, I’m sad to say, was stabbed to death by another inmate at Dozier. (I pay homage to this in the novel.)

I had never heard of the Dozier School for Boys, the horrific facility operating between 1900 and 2011, where countless boys were traumatized, sexually assaulted and sometimes—far too often—buried by other children in unmarked graves in the cemetery dubbed Boot Hill. I had never known that my mother had lost an uncle there—she may not have known herself. Another relative, who is a namesake of Robert Stephens, did not know for whom he had been named. After the tragedy and trauma of losing a child to incarceration, it was as if Robert Stephens had been erased from the world.

Soon after the call, my family was invited to Marianna to take part in the start of exhumations by University of South Florida forensic anthropologist Erin Kimmerle, who used the same imaging systems she used to find mass graves in war zones like Kosovo to try to find the buried boys of the Dozier School. (Last year, she also published her own book called We Carry Their Bones.) My husband, Steven Barnes, was there—along with our son, Jason, who was about nine at the time. My father, “Freedom Lawyer” John Dorsey Due, Jr., also came along—as he would on several research trips with me over the years, a way we could turn our mourning of my mother into an ACT rather than simply an emotional state.

After that first visit, I knew I had to write about Dozier. I met former prisoners, Black and white, who told me stories of bloody beatings in a whipping shed called “The White House.” They were suffering lifelong trauma. So, my father and I wanted to help tell the story of Robert Stephens and the Dozier School.

Shields: One of the many wonderful characters we closely follow in the novel is Robert’s sister, Gloria. Who did you look to and/or research as you developed her story?

Due: I had a very clear model for Gloria’s character. My late mother’s middle name was Gloria—Patricia Gloria Stephens Due—so whenever I wondered what Gloria should do next, I just asked myself “What would Mom have done?”

Mom laid down in front of garbage trucks to support striking sanitation workers in 1968–the cause for which Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., ultimately gave his life. In 1960, she and her sister, my Aunt Priscilla Stephens Kruize, were among eight Florida A&M University students who spent 49 days in jail rather than pay their fines after a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter. She wore dark glasses her entire life after being teargassed for leading a peaceful demonstration in 1960—a police officer recognized her as one of the organizers and said, “I want you!” before he threw teargas into her face. As a result, she suffered lifelong sensitivity to light.

My mother was my first superhero.

I asked myself what my 17-year-old mother would have done if her brother had been imprisoned under these circumstances—so if my agent made a suggestion that Mom wouldn’t have done, I had great clarity in saying, “Nope.”

Shields: In addition to your fiction, you’re also a screenwriter and producer. Can you discuss some of your projects for the screen and what the challenges and rewards are working in this medium?

Due: I began writing screenplays after I married my husband, Steven Barnes, who already had several writing credits and taught me a great deal. Beyond that, I studied great scripts while I watched the films and read Story, by Robert McKee, which is such a great book on story structure that I assign it to writing students even if they don’t write screenplays.

Over the years, my husband, Steven Barnes, and I have sold several television scripts and a few feature scripts together, most of which were adaptations of our own work. My first television credit was on Jordan Peele’s version of “The Twilight Zone,” a story called “A Small Town” that I co-wrote with Steve. Then we wrote two adaptations for an anthology film called Horror Noire: “The Lake,” based on my solo short story, and “Fugue State,” a short story we co-wrote. I was also very lucky to be brought on as an executive producer on Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror.

Steve and I currently are co-directing a short film adaptation of our feature script The Keeper with Blackmaled Productions and a Japanese producer called Samansa.

On the craft side, I love writing scripts! Scripts challenge a different part of my writer’s mind from a structural standpoint, and the emphasis on visual storytelling and dialogue really helps me sharpen those skills in my prose. On the business side, it’s very tough to sell scripts—so writing scripts is typically a much more frustrating undertaking for me than writing a short story or a novel, where at least I’m reasonably certain someone will see it one day!

Shields: There are people in our country who are actively trying to censor any discussion of the history of racism. Librarians in the Inland Northwest and farther afield have been doxed and worse for standing up for books that are deemed controversial. As an award-winning novelist and a co-author with your mother on a book about civil rights, what do you believe we lose when truth-telling stories are silenced, and what can we gain when they are narrated and uplifted?

Due: This is a lovely question! I often think of conversations with my late mother when I felt doubtful that I could make anything close to the kinds of contributions she had made to creating a better world because my true love was for writing. As an example of the power of the arts, she explained to me that during the height of the civil rights era in the 1960s, the NAACP made a strong commitment to trying to create representation in the arts because the arts matter. That’s why arts come under attack—enlightenment and knowledge lead to progress.

Since the end of the Civil War, there have been constant efforts to romanticize earlier eras of servitude for Black people and minimize the terrorism and barbarity at the root of slavery and Jim Crow. My mother forever warned about the “clock turning back” when she signed her books because she knew that power would not yield without a fight. Kudos to those brave teachers, parents, librarians, and artists who are fighting back against silence and ignorance with each story they help to share.

Shields: What are your favorite works in the horror genre at this time? What makes a great work of horror stand out for you?

Due: I appreciate horror more as I get older because I have a deeper understanding of how soothing it can be during horrific times. Whether it’s caregiving or watching democracy and human rights descend into shambles in the United States, horror enables us to use metaphors to express true-life dread through a looking glass that makes it feel less personal—and sometimes even redemptive. I love watching ordinary people stand up to forces that are seemingly greater than they are, which is how so many of us feel right now—and that journey was the joy of writing The Reformatory.

My favorite horror film at the moment is Ryan Coogler’s Sinners. I’ve already seen it four times, so I’m trying to wait before I watch it again, but it’s the perfect blending of music, metaphor, history, and horror.

In literature, I loved Model Home, by Rivers Solomon, and The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, by Stephen Graham Jones.

Sharma Shields is a novelist and the Chair for Spokane Is Reading. She is also the Writing Education Specialist for Spokane Public Library.

Tananarive Due is an American Book Award and NAACP Image Award-winning author, who was an executive producer on Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror for Shudder and teaches Afrofuturism and Black Horror at UCLA. Due is the author of several novels and two short story collections, Ghost Summer: Stories and The Wishing Pool and Other Stories. She is also coauthor of a civil rights memoir, Freedom in the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights, written with her late mother, Patricia Stephens Due. For more information about Due, visit simonspeakers.com and tananarivedue.com.

Tags: adults, author, author talk, books, reading, spokane is reading, teens