St. Pancras Station sparks imaginations

Posted on February 13, 2018 at 6:00 am

By Melissa Rhoades

What do filmmaker Christopher Nolan, the Spice Girls, and science-fiction author Douglas Adams have in common? They all found artistic inspiration in a building long considered an eyesore—a building I fell in love with at first sight.

Ever since borrowing books about castles as a grade schooler, I’ve been fascinated with buildings—how they look, change over time, and emotionally affect us. The Swiss architect Mario Botta said, “architecture is not just creating a space to protect people but to make them dream as well.”

Fiction writers have long understood this relationship between architecture and imagination. Take, for example, the crumbling estate Satis House in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Its dark passageways and cobwebbed rooms reflect the psychological stagnation of its withering inhabitant, Miss Havisham. In contrast, Bilbo Baggins’ clean and cozy abode in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit represents the comforts of home and Bilbo’s innocence.

In the Harry Potter series, King’s Cross Station (an actual London train station) functions as a place where magical and mundane worlds coexist. But J. K. Rowling wasn’t the first author to come up with this idea—and King’s Cross wasn’t the first train station to become a supernatural portal to a different world.

London’s St. Pancras Station, with its frontispiece, the Midland Grand Hotel (now the Renaissance London Hotel), plays a similar role in Douglas Adams’ 1988 Dirk Gently novel The Long, Dark Tea-Time of the Soul.

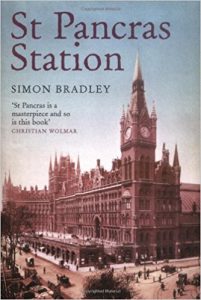

The Midland Grand Hotel was the epitome of neo-Gothic architecture and a symbol of Victorian greatness, designed by George Gilbert Scott and built in 1867–77. The adjoining St. Pancras railway station, designed by engineer William Henry Barlow, was the longest single-span roof in the world.

But by 1967, St. Pancras was seen as a bulging red carbuncle on the skin of swinging London. The station continued to function, but the hotel had been closed since the late 1930s. Its Gothic sensibilities didn’t resonate with modern culture. Close to oblivion, the building was granted protected, historical status less than two weeks before the wrecking ball was scheduled to knock it down.

Even after gaining protected status, the structure’s reputation continued to suffer. In 1978, the publication Private Eye referred to it as a “horrible, tatty old Victorian pile” (from the book St. Pancras Station by Simon Bradley).

In The Long, Dark Tea-Time of the Soul, Adams describes it as a “huge, dark Gothic fantasy of a building which stands, empty and desolate… its roof line a vast assortment of wild turrets, gnarled spires and pinnacles which seemed to prod at and goad the night sky” (pp 248–9).

Even the areas surrounding St. Pancras can fall under the influence of its architecture. Adams describes the surrounding neighborhood as:

“… an area where terrible things happen to people, to buildings, to cars, to trains… You could have a cheap car radio fitted while you waited, and if you turned your back for a couple of minutes, it would be removed while you waited as well. Other things you could have removed while you waited were your wallet, your stomach lining, your mind and your will to live. The muggers and pushers and pimps and hamburger salesmen, in no particular order, could arrange all these things for you.” (p 242)

As it turns out, some of the characters in the novel are also neglected has-beens. You see, some of Adam’s characters happen to be ancient gods stuck in a modern world that no longer has any use for them (a precursor of sorts to Terry Pratchett’s 1992 novel Small Gods). And, for some reason, these diminished immortals are magnetically attracted to St. Pancras Station.

I first glimpsed St. Pancras in 1989, from the window of a train pulling into the dilapidated station. As I disembarked, I immediately began to fall in love. Sure, there was soot, worn fixtures, and other signs of neglect—like the cheap plastic signs hung with no attention to aesthetics. But I also saw the intricate, open ironwork that spanned the ceiling of the massive train shed. Arches of patterned red and yellow stone delighted the eye. A frieze of tiles shimmered in stray shafts of light. The Booking Office’s wooden beams and Gothic windows lifted toward the sky.

In short, St. Pancras was a palace! It immediately transported me from the humdrum of public transportation to somewhere magical. Stepping outside from the dim interior, I was wowed again. The expanse of red brick seemed to extend forever. I couldn’t step far enough away to capture the whole colossus in my camera lens.

Just as this tattered, majestic place transported me, it also transports Adams’ grumbling, thundering, neglected gods. Where does it take them? You’ll have to read the novel to find that out. But I will share with you the fate of the hotel and train station.

Today, St. Pancras has again become a destination of cosmopolitan splendor. Through great effort and deliberation, it was restored and renovated between 1996 and 2007. St. Pancras International now serves as the Channel Tunnel’s high-speed Eurostar terminus, and St. Pancras Renaissance London Hotel once again offers grand accommodations to those who can afford it. According to a 2016 Washington Post article, when you visit “the sparkling St. Pancras rail terminal, you can sit at the longest champagne bar in Europe and raise your sparkling glass to a train departing for Paris.”

No one knows how Brexit will affect this rebirth, but for now St. Pancras is once more crowned in glory.

Douglas Adams didn’t live to see the renewal of this “huge, dark Gothic fantasy.” If he was still with us I am fairly certain that he could spin an equally enchanting tale about the gods who lounge now within its newly scrubbed and decorated walls.

As I mentioned, others have also been inspired by St. Pancras, and the building has made its way into films and videos. Its roles include the Arkham Asylum stairwell in Christopher Nolan’s 2005 film Batman Begins, the Mistlethwaite Manor staircase in the 1993 film production of The Secret Garden, and the location for the Spice Girls’ 1996 “Wannabe” music video. On YouTube, you can find videos on everything from the station’s history to tours to flash mobs to ghost stories.

In our Digital Library, you can learn more about St. Pancras Station, the Midland Grand Hotel, and the Renaissance London Hotel by searching for them in ProQuest.

What buildings spark your imagination?

Feature image credit: Credit: KevinAlexanderGeorge

Tags: Batman Begins, books, castles, Channel Tunnel, Chunnel, digital library, Douglas Adams, gothic, London, magical, movies, neo-Gothic, science fiction, Spice Girls, St. Pancras Station, The Secret Garden, towers, train stations